ZEITSPUREN

The Power of Now

9.9.-18.11.2018

Curated by SAMUEL LEUENBERGER and FELICITY LUNN

Time and its Discontents introduces us to the intersections of labour and social time. The works in this section build critical and playful narratives around current discontents of standardised living, work and leisure time. An early figure in the development of durational performance art, Tehching Hsieh displays in One Year Performance (1980–81) the documented evidence of a performance that chronicled a year of the artist’s life. To make the work, Hsieh followed a strict routine of punching a time clock every hour for 12 months, before presenting the individual images as a six-minute film with other forms of documentation. The tedium of industrial labour highlighted by Hsieh’s performance reinforces the dominance of western time structures that is investigated in Ragnar Kjartansson’s Scenes from Western Culture (2015). This employs six looped single-channel video tableaux to demonstrate Kjartansson’s fascination with the superficiality of cultural norms. Meanwhile David Horvitz’s The Distance of a Day (2013) breaks with the normal passage of time by juxtaposing videos of a single day made in different locations and time zones.

Sculpting Time examines the material processes of historiography with focus on the role of research in artistic methodologies. Artists revisit historical artefacts in order to draw out new meanings and associations. Kapwani Kiwanga’s Flowers for Africa (2014, 2017) reveal the artist’s interest in archival imagery of postcolonial independence celebrations. Finding that floral arrangements are a motif common to many of these photographs, for each venue where the work is exhibited Kiwanga commissions a local florist to recreate the bouquets as closely as possible. Flowers for Africa entertains a subjective response in the making and re-presentation of history. Similar manifestations of connectivity extend across many works in this section. Stéphanie Saadé’s Accelerated Time(2014) treats time as a physical property, making a mystery of the work’s broken fragments and the forces which produced them.

Capture: Staging the Live foregrounds the body as a site for expanding our perception of time, focusing on approaches to performance-based work. Pope.L’s practice takes the form of durational and endurance-based performances. The Great White Way, 22 Miles, 9 Years, 1 Street (2001–2009) is one of the artist’s best known «crawls» investigating exhaustion, in which he wore a Superman costume with a skateboard strapped to his back as he travelled the full length of Broadway, Manhattan’s longest street. Drawing frequently on sources from pop culture or philosophy, Sophie Jung produces marathon-length performances. For Come Fresh Hell or Fresh High Water(2017–18) the artist will activate different parts of her installation by reciting texts from memory, as well as employing stream-of-consciousness improvisation. Jung’s performance plays on the slippage between language and objects, transforming what the artist describes as a skewed format of « show and tell».

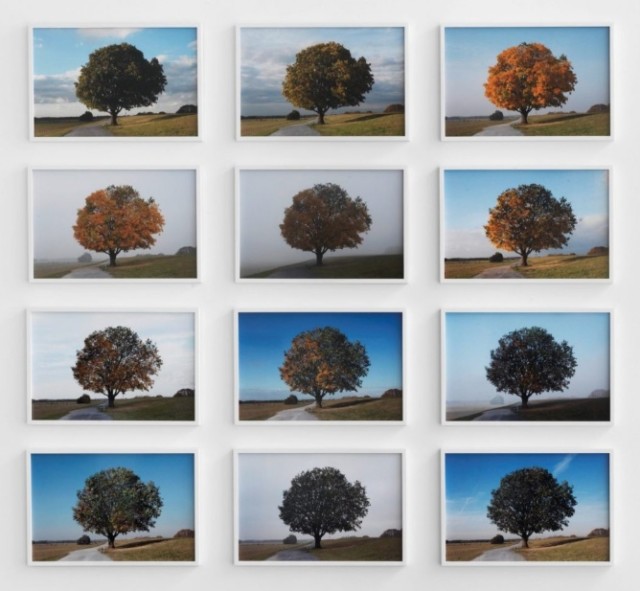

Finally, Speculative and Planetary Time analyses how digital connectivity and computerised technologies have radically shifted our experience of time. Works in this section reflect on deep time – time beyond the human – to speculate what new worlds might look like. Agniezska Polska’s My Little Planet (2016) combines animated daily-use objects floating in the cosmos with a humorous voice-over as a comment on the ways in which consumer culture dominates our world. The large-format photographs in Julian Charrière’s series First Light(2016–17) address the histories of nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll, making visible an atomic landscape within idyllic tropical island scenes. Where Charrière’s work turns our attention to the existence of radioactivity, Daniel Gustav Cramer’s Old Tjikko (2017) profiles «Old Tjikko» – the world’s oldest clonal tree located in Sweden’s Fulufjället National Park with roots thought to be almost 10’000 years old. Cramer explores how Old Tjikko functions as a myth deeply connected to the landscape and a symbol of endurance for our precarious planet.